MOSCOW: New

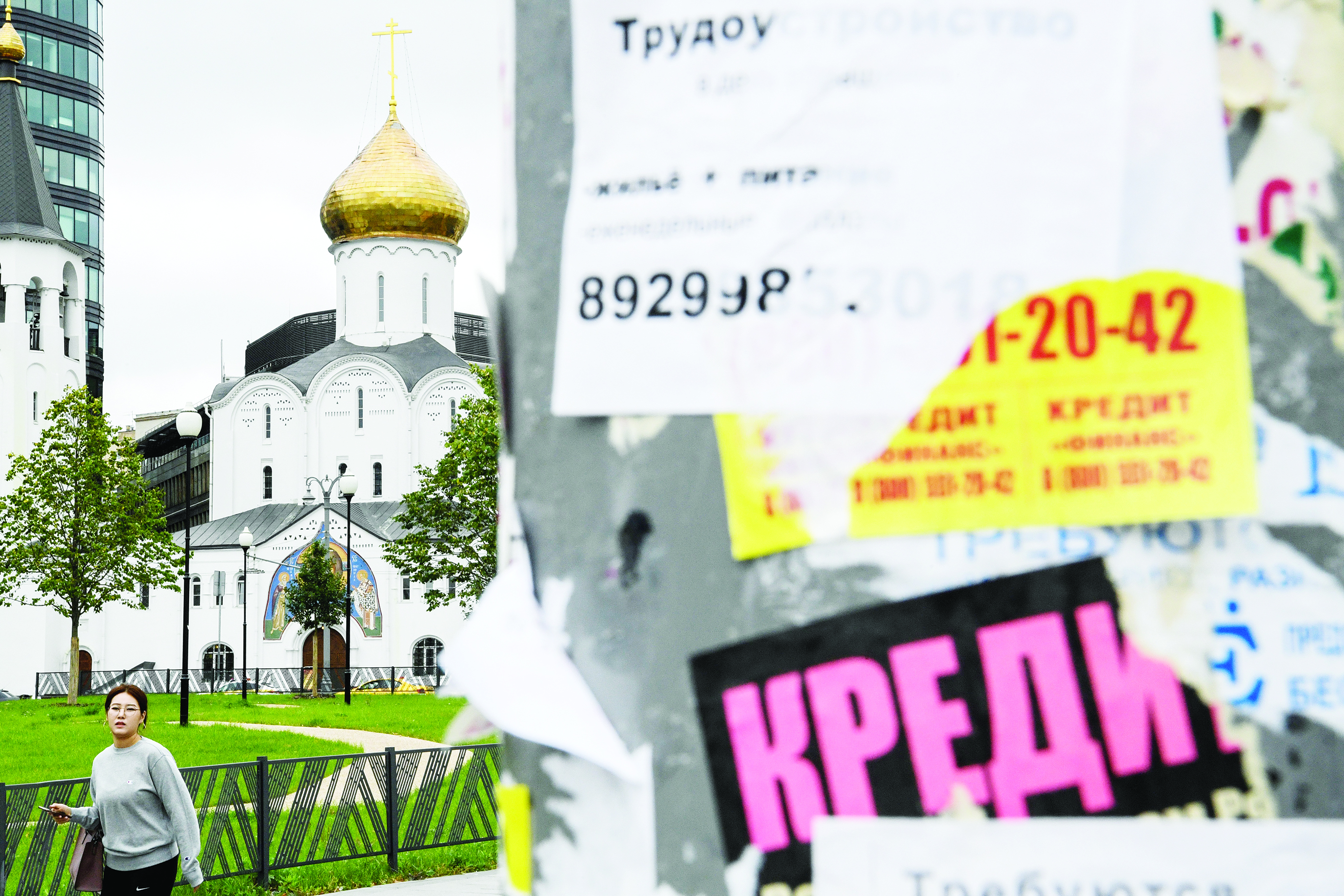

machines popping up in Russian shopping centers seem innocuous enough-users

insert their passport and receive a small loan in a matter of minutes. But the

devices, which dispense credit in Saint Petersburg malls at a sky-high annual

rate of 365 percent, are another sign of a credit boom that has authorities

worried.

Russians, who

have seen their purchasing power decline in recent years, are borrowing more

and more to buy goods or simply to make ends meet. The level of loans has grown

so much in the last 18 months that the economy minister warned it could

contribute to another recession. But it's a sensitive topic. Limiting credit

would deprive households of financing that is sometimes vital, and could hobble

already stagnant growth.

The Russian

economy was badly hit in 2014 by falling oil prices and Western sanctions over

Moscow's role in Ukraine, and it has yet to fully recover. "Tightening

lending conditions could immediately damage growth," Natalia Orlova, chief

economist at Alfa Bank, said. "Continuing retail loan growth is currently

the main supporting factor," she noted. But "the situation could blow

up in 2021," Economy Minister Maxim Oreshkin warned in a recent interview

with the Ekho Moskvy radio station. He said measures were being prepared to

help indebted Russians. According to Oreshkin, consumer credit's share of

household debt increased by 25 percent last year and now represents 1.8

trillion rubles, around $27.5 billion.

For a third of

indebted households, he said, credit reimbursement eats up 60 percent of their

monthly income, pushing many to take out new loans to repay old ones. Alfa

Bank's Orlova said other countries in the region, for example in Eastern

Europe, had even higher levels of overall consumer debt as a percentage of

national output or GDP. But Russian debt is "not spread equally, it is

mainly held by lower income classes," which are less likely to repay, she

said.

'People don't

have money'

The situation has

led to friction between the government and the central bank, with ministers

like Oreshkin criticizing it for not doing enough to restrict loans. Meanwhile, economic growth slowed sharply

early this year following recoveries in 2017 and 2018, with an increase of just

0.7 percent in the first half of 2019 from the same period a year earlier. That

was far from the 4.0 percent annual target set by President Vladimir Putin-a

difficult objective while the country is subject to Western sanctions. With 19

million people living below the poverty line, Russia is in dire need of

development.

"The problem

is that people don't have money," Andrei Kolesnikov of the Carnegie Centre

in Moscow wrote recently. "This is why we can physically feel the

trepidation of the financial and economic authorities," he added.

Kolesnikov

described the government's economic policy as something that "essentially

boils down to collecting additional cash from the population and spending it on

goals indicated by the state." At the beginning of his fourth presidential

term in 2018, Putin unveiled ambitious "national projects."

The cost of those

projects-which fall into 12 categories that range from health to

infrastructure-is estimated at $400 billion by 2024, of which $115 billion is to

come from private investment. A rise in value-added tax on January 1 that was

presented as crucial for the projects contributed to Putin's fall in popularity

over the last year. "If the debt bubble suddenly bursts, how will people

behave?" Kolesnikov asked.

"They will be left without money" while authorities continue

to spend on grand but ultimately unprofitable projects, the analyst warned.

He cited

grandiose "patriotic" undertakings such as a bridge connecting

Sakhalin island to the mainland in far eastern Russia, and the creation of a

"Russian Vatican" in the ancient monastery town of Sergiev Posad

outside Moscow. That will come at a "diabolical cost", he

quipped. - AFP