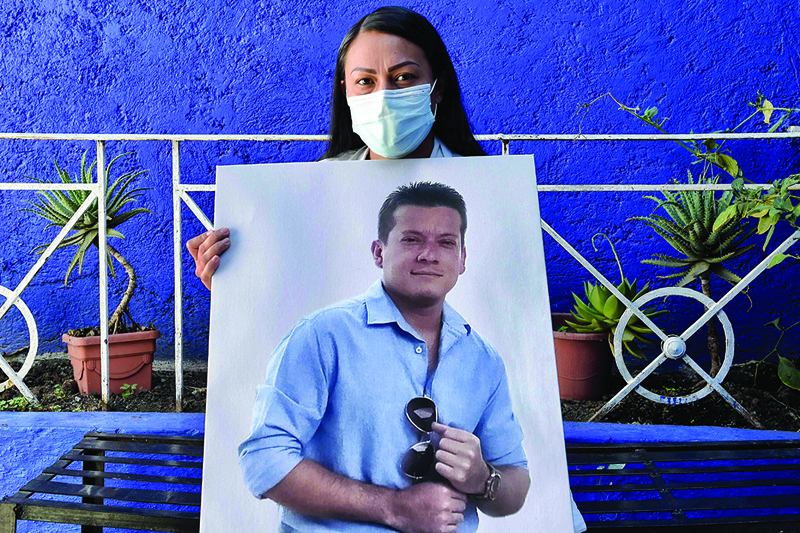

MEXICO CITY: Mexican doctor Yesenia Leyva and widow of Colombian doctor Christian Andres Cruz, poses with a picture of her husband, during an interview with AFP.-AFP

MEXICO CITY: Mexican doctor Yesenia Leyva and widow of Colombian doctor Christian Andres Cruz, poses with a picture of her husband, during an interview with AFP.-AFPMEXICO CITY: Christian Cruz specialized in intubation. Jesus de la Torre gave advice over the telephone to colleagues treating coronavirus patients. Diego Gutierrez worked long days examining tumors through a microscope. The three doctors are among several thousand heath workers who have died from COVID-19 in Mexico-which has the highest such toll in the Americas. The loss is not only irreparable for their families but also devastating for Mexico, one of the countries hardest hit by the pandemic and facing a shortage of specialists.

Cruz was an anesthesiologist of Colombian origin who specialized in inserting tubes in patients' airways to help them breathe. As the pandemic ripped through Mexico he found his services in ever higher demand in both the public and private hospitals where he worked. Cruz, who was 32 years old when he died on December 12, suffered from systemic sclerosis, an autoimmune disease that put him at heightened risk from the coronavirus. "We took extra care of ourselves," his widow Yesenia Leyva told AFP next to her husband's picture and the laryngoscope he used to intubate patients. "We all have a chance of getting sick from being exposed for so long, especially in our work," said Leyva, a 33-year-old pediatric oncologist.

'Heroic efforts'

As of March 1, Mexico had recorded 3,471 confirmed deaths among health workers from the coronavirus-nearly half of them doctors-and 230,000 infections. In total, around 195,000 lives have been claimed by COVID-19 in the country of 126 million people, which has the world's third highest death toll. The Pan American Health Organization reported in February that the number of health workers killed by COVID-19 in Mexico was more than twice that in the United States, which has the highest overall fatality toll. It said that 17 countries in the Americas had reported a total of 6,645 deaths among health workers as of last month.

The organization's director, Carissa Etienne, paid tribute to the huge sacrifices made by health workers-not just doctors and nurses but also orderlies, ambulance crews and cleaners. "Many have risked their own lives and those of their families to care for those who are sick, and their heroic efforts have saved many COVID patients," she said. Such dangers were part of the job for de la Torre, one of Mexico's most prominent emergency physicians who died on December 18 aged 67. "He was very dedicated," said his 43-year-old son Federico, who keeps one of his father's gowns and his laryngoscope to remember him by. "He sometimes missed birthdays and other family events to go into surgery or deal with medical issues."

In the first months of the pandemic, de la Torre kept going to the hospital where he worked in the central state of Morelos. Later, due to his age, he stopped but he still wanted to help. "He wanted to be there because it was something new for most of his colleagues," his son said. De la Torre decided to offer guidance by telephone to doctors on the frontlines, but even so he eventually caught the virus.

'Always together'

Ariadna Bautista sometimes wonders how the virus infected Gutierrez, her husband, who analyzed biopsies, mainly of tumors. His microscope still sits on his desk and his robe hangs on the chair where he would spend hours working until he fell ill and died on August 5. "I don't know how the virus got into the house," Bautista said. "I was the only one who went out."

Gutierrez avoided leaving the house because he was overweight, putting him at increased risk from the virus. So it was Bautista who went to the laboratory to collect samples for him to analyze. While Mexico's medical community lost a much-trusted specialist, Bautista lost the love of her life. "For me he was everything. We were always together. We did everything together," she said. - AFP