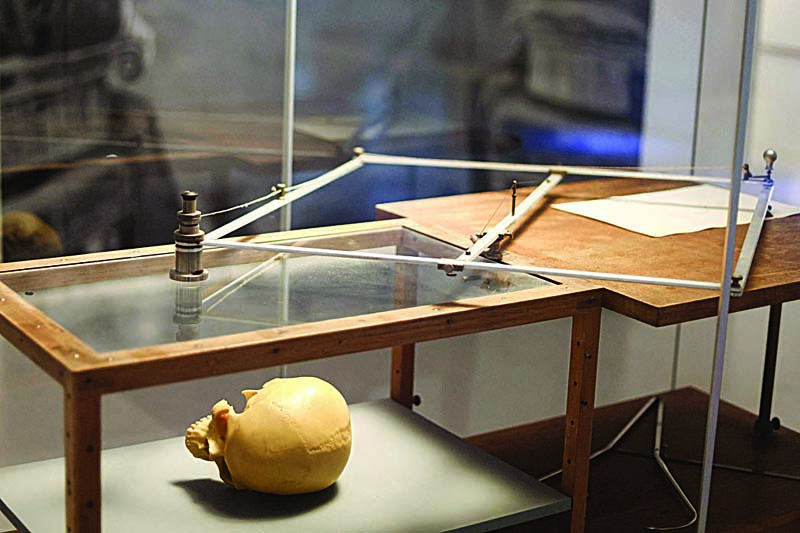

Photo shows a craniograph and skull measurement at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) during the temporary exhibition 'Human Zoo The age of colonial exhibitions' in Tervuren. - AFP photos

Photo shows a craniograph and skull measurement at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) during the temporary exhibition 'Human Zoo The age of colonial exhibitions' in Tervuren. - AFP photosIn the late 19th to early 20th centuries, recreated African villages were set up across Europe as amusement parks that served to extol the supposed cultural superiority of colonizing empires. They were also powerful vectors for racist stereotyping, as a Belgian museum show under way illustrates. "Human Zoo: The age of colonial exhibitions" at the Africa Museum outside Brussels until March next year has resonance, because its buildings are on the site where Belgium's King Leopold II in 1897 reconstructed three "Congolese villages" on royal grounds.

At the time, the Belgian Congo - today the Democratic Republic of Congo - was Leopold's private property and 267 men and women were taken from it by force to be put on show in Brussels' World Fair, made to sit in front of the dwellings. Seven of them died, from cold or sickness. That episode features in the museum's exhibition, which displays 500 items and documents showing what indigenous peoples suffered under various colonial powers.

The old ethnographic displays were designed to "show the other as primitive" and to "manufacture the 'savage'" to "reinforce the superiority of whites," the organizers explained. Measurements of skulls - craniometry - were used to support theories of "inferior races". The curators of the show estimate that the "industry" of putting human beings on display lured in around 1.5 billion people between the 16th century and 1960 to gawk.

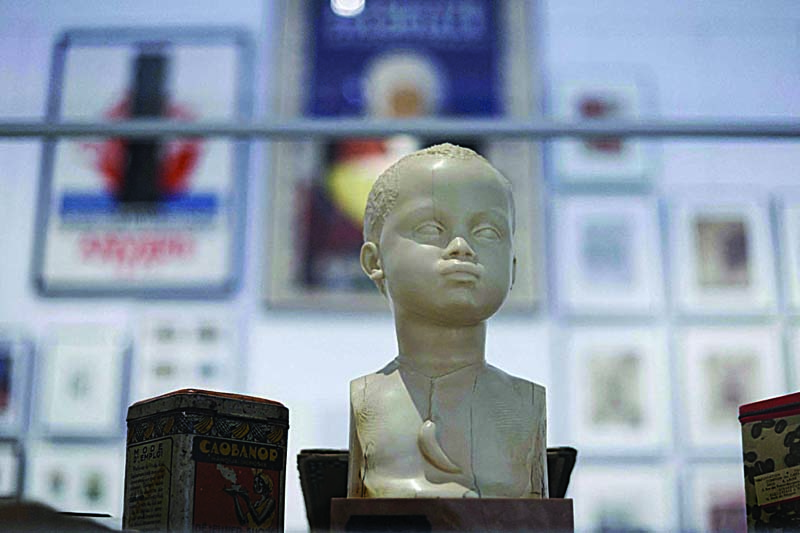

Photo shows an ivory bust at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) during the temporary exhibition 'Human Zoo The age of colonial exhibitions' in Tervuren.

Photo shows an ivory bust at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) during the temporary exhibition 'Human Zoo The age of colonial exhibitions' in Tervuren.'Freak show' roots

The reconstructed villages and the human "specimens" displayed in them owed part of their existence to "freak shows" where individuals with physical abnormalities - gigantism, dwarfism, or women with beards among others - were presented as spectacle by circus owner PT Barnum among others. In Europe, the "human zoos" reached their peak popularity from the 1880s after new colonial conquests. Imported exotic decors gave a curious public the impression of visiting real African villages. While Germany and France had already hosted their own "villages", Belgium got its first in 1885, near Antwerp, with 12 Africans.

Twelve years later their number grew 20 times bigger, and the colonial section of the World Fair in Brussels' satellite town of Tervuren attracted a million visitors. Over and over again, "the same message was repeated thousands of times, and the public ended up truly thinking that the African was a cannibal, inferior, dirty, lazy," one of the curators, Maarten Couttenier, told AFP. "And these stereotypes still exist today - proof that the colonial propaganda worked."

In the final part of the exhibition, the issue of how this racist denigration persists in everyday language challenges visitors with cliched phrases written in big letters on a white wall. "I love black people!" - "Oh, you did better than I expected" - "The apartment's already rented". For Salome Ysebaert, who conceptualised the museum's exhibition, such comments appear inoffensive and banal, but in reality are "microaggressions" revealing that racism is still lurking in minds, more than 60 years after the last "human zoo" in Brussels closed, in 1958. - AFP

Photo shows plaster casts from 'Live Congolese' by the artist Arsene Matton in 1911 at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) during the temporary exhibition 'Human Zoo The age of colonial exhibitions', in Tervuren.

Photo shows plaster casts from 'Live Congolese' by the artist Arsene Matton in 1911 at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) during the temporary exhibition 'Human Zoo The age of colonial exhibitions', in Tervuren.