KUWAIT: A vendor displays Zubaidi (silver pomfret) at the main fish market in Kuwait City. Kuwait's consumer price inflation edged down slightly to 3.2 percent y/y in July versus June. - AFP

KUWAIT: A vendor displays Zubaidi (silver pomfret) at the main fish market in Kuwait City. Kuwait's consumer price inflation edged down slightly to 3.2 percent y/y in July versus June. - AFPKUWAIT: Kuwait's consumer price inflation edged down slightly to 3.2 percent y/y in July versus June but has trended higher over the past year. Price increases in the food, clothing, transport and recreation segments continue to drive the headline rate. Strong consumer demand and pandemic-linked supply chain disruptions have caused inflation to surge globally.

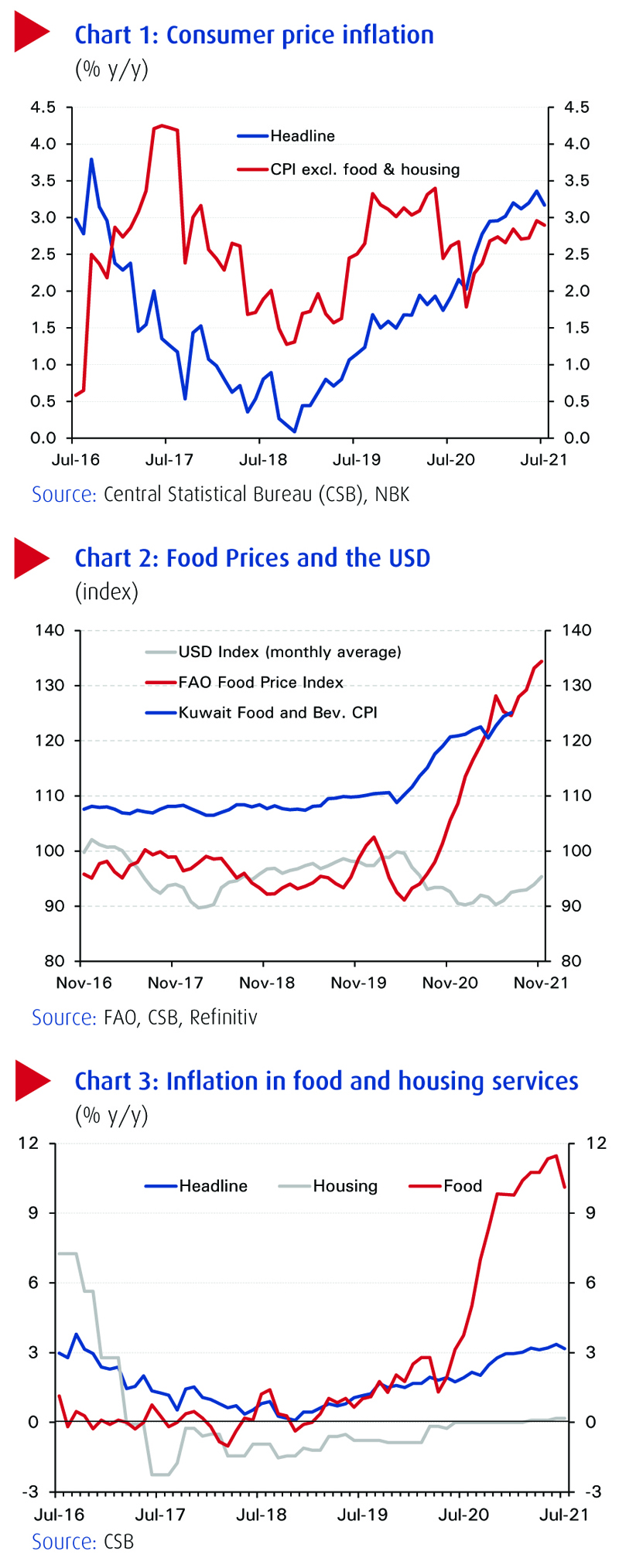

Recently released data from the Central Statistical Bureau (CSB) show that consumer price inflation moderated slightly in July to 3.2 percent y/y from 3.4 percent in June (+0.3 percent m/m). Still, inflation has trended higher so far this year and prices have now risen (m/m) in fourteen of the last fifteen months, driven by a combination of recovering demand, supply-side disruptions and higher international food prices.

Disruptions to global supply chains is a worldwide phenomenon, as pandemic-linked economic reconfiguration and worker shortages struggle against the surge in post-lockdown consumer spending. Similar factors (as well as higher energy prices) have also pushed up inflation in a range of developed countries to much higher levels of late, including the eurozone (4.9 percent, November) and the US (6.2 percent, October).

Food prices

Price pressures in Kuwait have been most pronounced in the food and beverages category, which in July climbed 10.1 percent y/y. Price increases were recorded across most sub-indices but the largest was observed in the fruits (+25 percent), vegetables (+9.7 percent) and meat (+15.3 percent) categories. Some of this is a reflection of higher international food prices more generally. The Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) Food Price Index, a global food price barometer, was up 33 percent y/y in July (and it remained high in November).

Upward price pressure on international food (and commodity) prices also stemmed from the US dollar's depreciation, especially over April and May: generally, a weaker dollar makes the price of USD-denominated foods and commodities more affordable for importers using other currencies, stimulating demand. However, the dollar has strengthened since then, suggesting that any such impact on food prices may have gone into reverse.

Meanwhile, prices in the housing services category - mostly rents - climbed only 0.2 percent y/y in July. A minor monthly rise was recorded on the back of an increase in 'services and maintenance repairs', perhaps a reflection of higher construction/raw material costs. Recorded housing rents have barely changed in two years, yet even this minimal change seems on the high side relative to expectations: anecdotal evidence points to rent discounts being offered to both existing tenants (temporarily for a few months) and prospective tenants during the pandemic period. Indeed, in other Gulf countries, housing subcomponents of inflation indices have witnessed substantial declines.

Housing segment

Meanwhile, core inflation (i.e. excluding food and housing) has also risen modestly so far this year, reaching 2.9 percent y/y in July versus 2.7 percent in December 2020, though dipping slightly versus June (3.0 percent). Inflation in the transport (+5.4 percent), clothing (+6.5 percent) and recreation (+8.2 percent) categories continued to trend upwards.

Transport prices were at a 3-year high, driven largely by the 'Travel by Air' component, which saw a 25 percent y/y increase on surging ticket prices following the partial lifting of travel restrictions towards the end of 2Q21 (this may have eased in subsequent months on expanded flight availability). Prices in the recreation category experienced the highest inflation due primarily to an increase in the cost of personal computers and laptops, while computer-based learning and remote working were on the rise during the pandemic.

In contrast with the increase in price for most core components, education costs continued to record annual declines of 15.5 percent, after the Ministry of Education announced in September 2020 reductions of up to 25 percent in private school fees during the pandemic as physical schooling was replaced by online schooling. However, with students now largely back at school tuition fees have reverted, and this should be visible in the September and October CPI.

Wholesale prices

Wholesale price inflation, which measures the prices charged between businesses (rather than from businesses to consumers), stood at a 3-year high of 1.5 percent y/y in June 2021, according to the CSB. This was slightly higher than the reading of 0.8 percent at the end of the previous quarter. Inflation in the price of imported goods was also at a 3-year high in June, at 2.1 percent, while prices for locally-produced goods were up 0.6 percent.

Similarly, the producer price index, which measures changes in the price of goods bought and sold by producers, in June reached its highest level since October 2018 (100.1), increasing by 75 percent y/y. However, much of this was driven by the higher price of oil: prices in the oil extraction segment rose 104 percent y/y. Prices in the manufacturing segment increased by 49 percent y/y, although this was skewed by big rises in the refining segment, which is also linked to oil prices. Upward pressures were not universal however: prices in some other manufacturing segments, including chemicals and electrical equipment, were actually down y/y.

Overall, domestic inflation so far this year has come in slightly higher than expected and internationally, upward pressures look set to persist for longer than previously anticipated. Personal consumption has been on a tear, supported by strong household savings rates, worker shortages are an issue in some sectors (leading to higher business costs which are then passed on to consumers) and global supply chains are taking longer than expected to untangle. These factors, along with the higher education costs from September, mean that the risks to our 2021 year-average inflation forecast for Kuwait of 2.6 percent are to the upside: a figure of around 3.0 percent looks more likely.

Looking ahead to 2022, inflation will ultimately be shaped by several factors: the pace of the global and local economic recovery amid a potential resurgence of COVID-19 infections (including the recent discovery of the potentially more infectious Omicron strain); the potential easing in supply-side frictions; the direction of commodity prices; and the extent and speed of monetary policy tightening by central banks around the world in an effort to dampen inflation.

In Kuwait, our base case is for inflation to ease slightly from 2021 levels, with non-oil growth expected to slow from this year's expected rebound, current record rates of consumer spending moderating and as the government adopts a more restrained spending stance amid expectations of lower oil prices.