ALGIERS/CAIRO/JAKARTA/RIYADH: Days before the holy fasting month of Ramadan begins, the Islamic world is grappling with an untimely paradox of the new coronavirus pandemic: Enforced separation at a time when socializing is almost sacred. The holiest month in the Islamic calendar is one of family and togetherness - community, reflection, charity and prayer. But with shuttered mosques, coronavirus curfews and bans on mass prayers from Senegal to Southeast Asia, some 1.8 billion Muslims are facing a Ramadan like never before.

Across the Muslim world the pandemic has generated new levels of anxiety ahead of the holy fasting month, which begins on Friday. In Algiers, Yamine Hermache, 67, usually receives relatives and neighbors at her home for tea and cold drinks during the month that Muslims fast from dusk till dawn. But this year she fears it will be different. "We may not visit them, and they will not come," she said, weeping. "The coronavirus has made everyone afraid, even of distinguished guests."

In a country where mosques have been closed, her husband Mohamed Djemoudi, 73, worries about something else. "I cannot imagine Ramadan without taraweeh," he said, referring to additional prayers performed at mosques after iftar, the evening meal in which Muslims break their fast. In Jordan the government, in coordination with neighboring Arab countries, is expected to announce a fatwa outlining what Ramadan rituals will be permitted, but for millions of Muslims, it already feels so different.

From Africa to Asia, the coronavirus has cast a shadow of gloom and uncertainty. Millions are locked down across the Middle East - from Saudi Arabia and Lebanon to the battle zones of Libya, Iraq and Yemen. Around the souks and streets of Cairo, a sprawling city of 23 million people that normally never sleeps, the coronavirus has been disastrous. "People don't want to visit shops, they are scared of the disease. It's the worst year ever," said Samir El-Khatib, who runs a stall by the historic Al-Sayeda Zainab mosque, "Compared with last year, we haven't even sold a quarter."

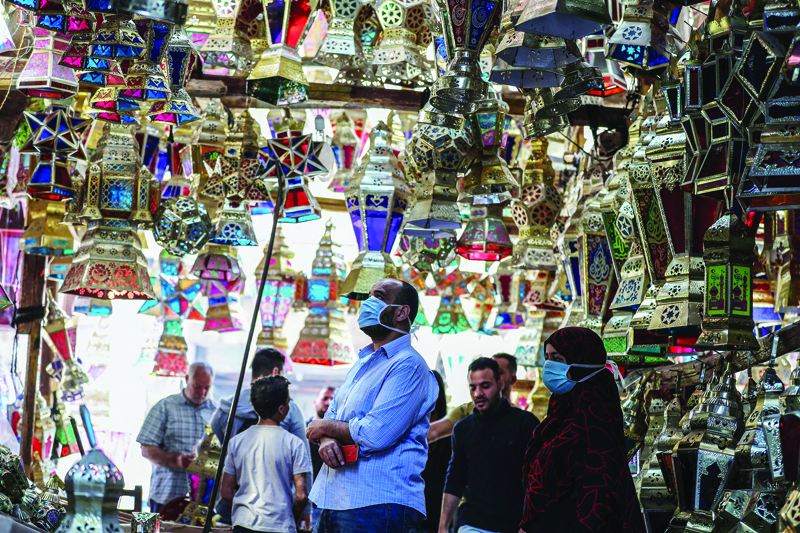

During Ramadan, street traders in the Egyptian capital stack their tables with dates and apricots, sweet fruits to break the fast, and the city's walls with towers of traditional lanterns known as "fawanees". But this year, authorities have imposed a night curfew and banned communal prayers and other activities, so not many people see much point in buying the lanterns. Among the few who ventured out was Nasser Salah Abdelkader, 59, a manager in the Egyptian stock market. "This year there's no Ramadan mood at all," he said. "I'd usually come to the market, and right from the start people were usually playing music, sitting around, almost living in the streets."

The Egyptian capital's narrow alleys and downtown markets are covered with traditional Ramadan decorations and brightly colored fawanees. These decorations also typically adorn restaurants and cafes, but they are all closed due to the outbreak, lending a more subdued feel to the city as the holy month approaches. Dampening the festivities before they begin, the coronavirus is also complicating another part of Ramadan, a time when both fasting and charity are seen as obligatory.

In Algeria, restaurant owners are wondering how to offer iftar to the needy when their premises are closed, while charities in Abu Dhabi that hold iftar for low-paid South Asian workers are unsure what to do with mosques now closed. Mohamed Aslam, an engineer from India who lives in a three-bedroom apartment in downtown Abu Dhabi with 14 others is unemployed because of the coronavirus. With his apartment building under quarantine after a resident tested positive, he has been relying on charity for food.

In Senegal, the plan is to continue charity albeit in a limited way. In the beachside capital of Dakar, charities that characteristically hand out "Ndogou", baguettes slathered with chocolate spread, cakes, dates, sugar and milk to those in need, will distribute them to Quranic schools rather than on the street.

Meanwhile in Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim-majority country, some people will be meeting loved ones remotely this year. Prabowo, who goes by one name, said he will host Eid al-Fitr, the celebration at the end of the fasting month, via the online meeting site Zoom instead of flying home. "I worry about the coronavirus," he said. "But all kinds of togetherness will be missed. No iftar together, no praying together at the mosque, and not even gossiping with friends."

Several countries' religious authorities, including Saudi Arabia's Grand Mufti Abdulaziz Al-Sheikh, have ruled that prayers during Ramadan and Eid be performed at home. "Our hearts are crying," said Ali Mulla, the muezzin at the Grand Mosque in Makkah. "We are used to seeing the holy mosque crowded with people during the day, night, all the time… I feel pain deep inside."

In recent weeks, a stunning emptiness has enveloped the sacred Kaaba - a large black cube structure draped in gold-embroidered cloth in the Grand Mosque towards which Muslims around the world pray. The white-tiled area around the Kaaba is usually packed with tens of thousands of pilgrims. Ramadan is considered an auspicious period to perform the year-round umrah pilgrimage, which Saudi authorities suspended last month. It is likely the larger hajj pilgrimage, set for the end of July, will also be cancelled for the first time in modern history after Saudi Arabia urged Muslims to temporarily defer preparations.

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and the Palestinian Territories Muhammad Hussein has announced similar prayer restrictions during Ramadan, while also advising against the public sighting of the crescent moon, which is used to estimate the start of the holy month. The restrictions are in line with the recommendations of the World Health Organization, which has urged countries to "stop large numbers of people gathering in places associated with Ramadan activities, such as entertainment venues, markets and shops".

The restrictions have hit businesses hard, including retailers catering to the typical rush of Ramadan shoppers. This year many Muslims have repurposed their Ramadan shopping budgets to stock up on masks, gloves and other COVID-19 protective gear. "I had saved up an amount to spend on Ramadan shopping, but I spent it instead on purchasing things needed for quarantine and protection against the virus," said Younes, 51, who works at a clothing store in the Syrian capital Damascus. "This year, no feasts, no visits… I feel we are besieged by the virus wherever we go."

Sanctions-stricken Iran last week allowed some shuttered Tehran businesses to reopen, despite being one of the worst-hit countries in the Middle East, as many citizens face a bitter choice between risking infection and economic hardship. Official statistics show the disease has killed more than 5,000 people and infected over 80,000 in Iran, but the actual figures are thought to be higher. Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has appealed to Iranians to pray at home during Ramadan, while urging them to "not neglect worship, invocation and humility in our loneliness".

Hardliners across the region have rejected some online suggestions by Muslims that they should be exempt from fasting this year owing to the pandemic, insisting that while social distancing was necessary, the virus did not stop them from observing the rules of Ramadan from home. "No studies of fasting and risk of COVID-19 infection have been performed," the WHO said in its list of recommendations. "Healthy people should be able to fast during this Ramadan as in previous years, while COVID-19 patients may consider religious licenses regarding breaking the fast in consultation with their doctors, as they would do with any other disease."

For many trapped in their homes in war-battered countries such as Libya, Ramadan is still a time for prayer, introspection and charity. "For me, Ramadan has come early this year. During these curfew times, it means fewer working hours, similar to Ramadan," said Karima Munir, a 54-year-old banker and mother of two in Libya. "Ramadan is always about being charitable and this year the needy are numerous, especially with the (displacement) from the war." - Agencies