When leaving is not an option, survival becomes a daily struggle- People from the newspaper were telling everyone that nothing serious was going to happen

- When I reached [the office] I saw my editor crying. People were in total shock

- The telephone was answered by an Iraqi soldier who told me that they were now in control of Kuwait

- We had to sell some of our gold and everything we had so we could eat

- Many Kuwaitis were afraid, but some expats protected them

- We thought that going home is the only way to survive

- Kuwait was in complete darkness at that time because the oil fields were on fire

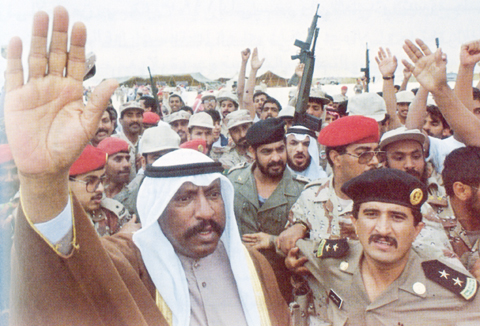

Then Crown Prince His Highness Sheikh Saad Al-Abdullah A-Sabah cheers with Kuwaiti soldiers following Kuwait’s liberation

Then Crown Prince His Highness Sheikh Saad Al-Abdullah A-Sabah cheers with Kuwaiti soldiers following Kuwait’s liberationKUWAIT: At 6:00 am, Ghazi Qaffaf was woken by the frantic ring of his home telephone. It rang and rang, forcing Qaffaf out of bed to answer the call. It was a friend from his homeland, Jordan, who was checking in; he had heard that the Jordanian International Airport had cancelled flights to Kuwait because of an invasion. Qaffaf assured his friend that nothing was happening in Kuwait. Then he got another call, this time from his cousin in America, wanting to know if the Iraqis had indeed breached the border. "[I was] in shock," Qaffaf said. "My manager called, [and] his voice was in panic mode. I only remember his urgent call to report immediately, [and] left home without washing my face."

Qaffaf was 28 when Iraq invaded Kuwait. The night before the attack, then Crown Prince His Highness Sheikh Saad Al-Abdullah A-Sabah was in Saudi Arabia for a meeting. Qaffaf, now 55, was working as a photographer for Al-Watan newspaper at the time. "The night before the invasion, I was assigned to take photos of that meeting from a live TV feed from Saudi Arabia broadcasted by Kuwait Television (KTV)," he said. "At that time [there was] no internet, no cable to carry the important meetings like that, so normally we took pictures from the official KTV footage."

There was no hint that something big was going to happen the following day. "I went home just the same. [There was] no serious scenario except the lingering noise about Iraqis preparing to invade Kuwait. That had become normal in the heads of many here."

Before Qaffaf left at around nine that evening, he saw a Reuters report reading "Urgent ... urgent ... urgent," but did not fully appreciate its significance; similar messages had arrived "many times" before. "People from the newspaper were telling everyone that nothing serious was going to happen, that we should go home and get a good night's sleep," he recalled. "During the night, I was watching Iraqi TV and heard strong messages. But to me, it was the same noise I had heard many times before. It was a normal night, and I slept with my family."

Panicked faces

Early that morning, the phone rang. On the way to work, Qaffaf remembers the panicked faces of the people he passed. "I saw people weeping, people running. I heard people cursing Iraqis ... When I reached [the office] I saw my editor crying. People in the newspaper were in total shock," he said. Word was going around that the Ministry of Information had fallen, and Qaffaf decided to contact a friend who worked there. "The telephone was answered by an Iraqi soldier who told me that they were now in control of Kuwait."

Qaffaf's instinct to take photos pushed him to head to the army headquarters located just a few kilometers away. On route, he heard a heavy bombardment that turned out to be targeting his destination. "The headquarters were on fire, I could see the smoke billowing from that direction," he recalled. "At the same time, Kuwaiti military planes were hovering above." He heard that there were Iraqi forces at the headquarters, some on the Jahra road, but that all were heading towards Kuwait City. He quickly took a few pictures and retreated to the office in Al-Watan.

On arrival, he was met with an entirely empty workspace, save for his supervisor. There would be no newspaper the following day, he was told, so he should leave. Qaffaf described it as the saddest moment in his career; the photos of the burning headquarters were worthy of running on the front page the following day. He went straight to develop the negatives from his camera, then headed home. "On my way home, I saw cars abandoned in the street. People were in a hurry, some were crying out to Allah ... There were very few private vehicles on the road, but I noticed several Iraqi tanks on the streets."

Qaffaf's arrival calmed his family's panic. They were listening to every piece of news they could access over the radio, and Qaffaf heard Sheikh Saad's call to defend the homeland. But he also remembers the high spirits of the Iraqi soldiers on television. "They were dancing in front of the camera and declaring that they had already conquered Kuwait and liberated its people. Kuwait, they said, was now under the control of the Iraqis."

Not an option

In the days and months that followed, Qaffaf and his family mainly stayed indoors. He briefly attempted to return to the office, but there was no hope of publishing anything. Friends from Jordan called and tried to convince him to leave Kuwait, his birthplace, but despite holding Jordanian citizenship, a move would be impossible. He had two children at the time, as well as his mother and father to think of. Splitting the group up was not an option, and he could not simply uproot to begin a new life elsewhere.

Qaffaf's money was in the bank, and inaccessible. He had around KD20 in cash, so as the invasion continued, the family's chance of survival grew slimmer. "We had to sell some of our gold and everything we had so we could eat," he recalled.

The situation deteriorated from there. Six months after the Iraqis arrived, the family's electricity was cut, while food was reduced to soup and rice. Qaffaf had to brave queues that stretched for hours to pick up minimal supplies. It was the only way to survive.

Qaffaf heard that Iraqi soldiers were looking to kill Kuwaiti nationals. "Many Kuwaitis were afraid, but some expats protected them," he recalled. Then, a month later, he heard the news he had been waiting for. Everyone could come out of hiding, the radio said. Kuwait was free. No one from Qaffaf's family had been harmed.

He returned to the office two days later, only to find it badly damaged. "Documents were ransacked, papers were spewed all over," he said. "Everything was destroyed ... It was like a hell, but I was overwhelmed by the fact that Iraqis had left Kuwait."

He and his colleagues began the process of cleaning up, and published their first post-invasion copy ten days after the liberation. The same impulse to photograph events took over. "I started taking pictures of the Iraqi damage. Everything was black. The sky was black because of the burning oil refinery at Mina Abdullah. Then, slowly, everything went back to normal."

Very strange environment

On the morning of August 2, Bong Pagutayao, a Filipino cashier at a grocery store, set out for work, ignoring news that something was terribly wrong in Kuwait. He thought it was going to be a regular day. As he waited for the bus to Kuwait City, he noticed silence, only broken by the sounds of bombardment not far away. He noticed the massive movements of tanks but very few civilian vehicles. After 15 minutes at the bus stop, he went home. "I noticed a very strange environment," he said. "There was clearly something big brewing, so after a few minutes I rushed back home."

Pagutayao's flatmates, also Filipinos, were awake, huddled around the radio. One Arab colleague was translating the news from Kuwaiti radio, which was under Iraqi control at the time. "They were urging people in Kuwait to cooperate and avoid being a hindrance," he recalled.

Some of them wanted to leave Kuwait immediately. "When I returned home, everyone in the flat was awake and stunned. They had been discussing what to do next," he said. Some had decided to leave Kuwait to avoid the violence, but Pagutayao and his flatmates had other ideas. "In my mind I said, I will stay whatever happens. No-one from our flat left, we all stayed until the war's end."

After 30 days, the 20 Filipinos who lived in Pagutayao's flat had run out of food. The only way to survive was to accept temporary work offered by the occupying forces. "Some of us quickly accepted the job and were working," he said. Pagutayao, however, was more hesitant, but eventually accepted work in exchange for food. They rotated shifts in a meat factory, some working during the day, others during the evening.

Evacuation plan

The safety of expats in Kuwait worsened day-by-day, especially after the US-led coalition entered the scene. News about people being killed in the fighting also continue apace. "We thought that going home is the only way to survive," Pagutayao said. "All of us in the flat decided to leave Kuwait. We went to our embassy in Jabriya and the officials were preparing to evacuate most Filipino nationals. Cars were parked in front of the embassy waiting for the go signal to leave."

On the road to Abdaly, the group was stopped by an Iraqi commander who warned them that there were heavy bombardments on the border and it was not safe to cross it. Their chance to leave Kuwait had gone. They returned to Adailiya, still without a steady supply of food. Adailiya was mainly populated by Kuwaitis, many of whom were afraid to leave their homes, which meant that the Filipino group were able to exchange food for favors.

Things remained that way until they heard Kuwait had been liberated. "Kuwait was in complete darkness at that time because the oil fields were on fire, but we joined in the joy of the liberation," he recalled. "Then, jobs were offered in abundance. Money was easily earned and people were kind and gracious." After the liberation, Bong went on to work in a travel agency, a cargo forwarding company, and then with the KTV2 marketing team, where he remains today.

By Ben Garcia