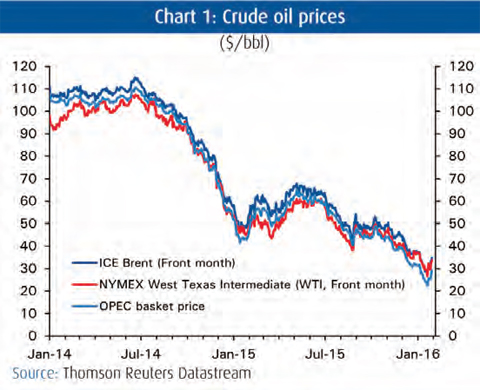

KUWAIT: Market bears continued to dominate going into the new year, sending benchmark crude oil prices to a 12-year low in January. Amid a 'perfect storm' of unremitting crude oversupply, continuing stock builds, weakening China-centered emerging market growth and a strengthening US dollar, ICE Brent, the international marker, fell to $27.8 per barrel ($/bbl) on 20 January, a level last seen in November 2003. Similarly, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the US benchmark, dropped to $26.5/bbl. Prices looked to have recovered somewhat by month's end, however, with Brent rising by 24% to $34.7/bbl after it was reported that OPEC and Russia might consider a coordinated production cut.

KUWAIT: Market bears continued to dominate going into the new year, sending benchmark crude oil prices to a 12-year low in January. Amid a 'perfect storm' of unremitting crude oversupply, continuing stock builds, weakening China-centered emerging market growth and a strengthening US dollar, ICE Brent, the international marker, fell to $27.8 per barrel ($/bbl) on 20 January, a level last seen in November 2003. Similarly, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the US benchmark, dropped to $26.5/bbl. Prices looked to have recovered somewhat by month's end, however, with Brent rising by 24% to $34.7/bbl after it was reported that OPEC and Russia might consider a coordinated production cut.

In the futures markets, January was a particularly volatile month, with hedge funds and speculators seesawing between long and short positions. Towards the end of the month, many bearish positions were being reversed amid renewed optimism about a potential supply cut. Brent prices for delivery in 2017 and 2018 were ranging between $41-$46/bbl, slightly below the consensus of analyst's forecasts.

Nevertheless, despite the four-day rally at the tail end of January, market sentiment remains overwhelmingly bearish and reflective of the issue at the heart of the oil price downturn: persistent crude oversupply. With Iran recently unshackled from international sanctions and looking to bring at least another 500,000 barrels per day (b/d) of crude to markets by mid-2016, any relief that may have been coming from a potential decline of 600,000 b/d of non-OPEC supply, as per the International Energy Agency's (IEA) forecasts, may have to be delayed until 2017 at the earliest.

Indeed, the IEA reckons that 2016 could be the third year in a row that supply will exceed demand by 1.0 mb/d, with the imbalance only beginning to unwind in late 2016 and early 2017. Oil prices are therefore likely to remain under pressure for longer, and would require a sooner-than-expected production cut by OPEC (in tandem with Russia) or a steeper decline in US shale output to see any significant rise. A supply disruption arising from a major geopolitical incident remains another possibility; with OPEC spare production capacity at historically low levels in relation to global supply (just shy of 2.5 percent), any disruption to supply could have an outsized impact on the oil markets.

However, judging by the ease with which markets shrugged off the spike in tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia relating to the execution of the Shia cleric Nemr Al-Nemr in January, markets' tolerance of geopolitical risk may be higher than previously assumed.

Oil demand growth

World oil demand growth is expected to slow back down to its long-term average of 1.2 mb/d in 2016, after peaking at a five-year high of 1.8 mb/d in 2015, the IEA has estimated. The stimulus of lower oil prices on oil demand has begun to fade, while warm winter weather in the northern hemisphere has suppressed the traditional seasonal boost to oil demand (for heating oil). Macroeconomic conditions have also weakened in several emerging markets and commodity-dependent exporters including China, Brazil and Russia.

Elevated OPEC production

According to data obtained via OPEC secondary sources, OPEC production fell by 190,000 b/d in December to 32.2 mb/d. (Chart 4.) This figure now includes output from Indonesia after the country was readmitted to the group as its 13th member at the 4 December meeting.

Saudi Arabia posted the largest decline among OPEC's Arab producers, with output slipping by 40,000 b/d to 10.1 mb/d. (Chart 5.) December marked the tenth consecutive month that the kingdom pumped more than 10 mb/d, bringing the kingdom's annual average to an all-time high of 10.2 in 2015.

Riyadh remains deeply committed to protecting its market share in the current low oil price environment, so any potential cut in OPEC production would likely be contingent on the Saudi-led group securing the participation of non-OPEC nations such as Russia. And even then, it is by no means certain that individual country production quotas will be adhered to.

Production in neighboring Gulf countries, with the exception of Kuwait, showed slight gains compared to November. Output in the UAE and Qatar increased by a relatively small 10,000-20,000 b/d to settle at 2.9 mb/d and 0.67 mb/d, respectively. Kuwaiti output dropped by 10,000 b/d to 2.7 mb/d in December.

Looking ahead to the rest of 2016, gains in OPEC production are likely to come mainly from Iran, now that the Islamic Republic has been freed from international sanctions. The Iranian authorities seem confident of returning quickly to international markets with at least 500,000 b/d in the next few months and an additional 500,000 b/d by year-end. This would bring Iran's production back to its pre-sanctions level of 3.7 mb/d. Most observers reckon that this target is too optimistic given the weakened state of oil infrastructure in the country.

Decline in US shale output

World crude supply expanded by 2.6 mb/d in 2015, following gains of 2.4 mb/d in 2014. (Chart 6.) For 2016, however, all eyes will be on non-OPEC output and the supply response to low oil prices. Having expanded by 1.2 mb/d in 2015, non-OPEC supply is expected to contract by 600,000 b/d this year, according to the IEA. This is largely predicated on output moderating in the US, where hitherto resilient US shale production is finally beginning to suffer from cutbacks in capital spending and falls in oil rig activity.

The most recent data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) showed that US crude output growth in 2015 had slowed to 0.9 percent, or 81,000 b/d, from 12.3 percent in 2014. According to weekly data provided by the EIA, US crude output fell from a high of 9.6 mb/d in June 2015 to 9.2 mb/d as of 22 January 2016, a decline of 389,000 b/d, or 4.0 percent.

Oil markets are bracing themselves for a volatile year. Uncertainty surrounds OPEC's potential production response, including the additional volumes of crude Iran is likely to bring to the market, and the extent to which non-OPEC supply will be negatively affected by the oil price downturn. While there seems to be greater scope for prices to rise in view of all of the above, it cannot be taken for granted that oil prices reached their bottom in January.